Between the commas, a life defined

Obituaries focus on achievement. That's not the only standard.

My longtime Houston Chronicle colleague Tony Freemantle observed that the impact of a life could be measured by “what’s between the commas” in a newspaper obituary. He referred to a format that is used frequently in “news obits” — that is, stories written by journalists about deaths of people whose passing is deemed newsworthy, as opposed to paid death notices typically written by loved ones.

Here’s the news obit formula: Name of deceased, (comma), summary of what this person did, said or created that’s considered important, (comma) , died (date) in location and cause of death, if known and disclosed. (New sentence) He or she was (age.)

(Always “died;” never a euphemism like “passed away.”)

The words between the commas typically summarize the person’s achievements. Sometimes the writer makes choices that make this analysis a bit more complicated. Here’s the first paragraph (the “lede,” in goofy newspaper-speak) of the New York Times obituary of the actress Diane Keaton:

Diane Keaton, the vibrant, sometimes unconventional, always charmingly self-deprecating actress who won an Oscar for Woody Allen’s comedy “Annie Hall” and appeared in some 100 movie and television roles, an almost equal balance of them in comedies like “Sleeper” and “The First Wives Club” and dramas like “The Godfather” and “Marvin’s Room,” has died. She was 79.

So, five commas. A lot to unpack. The commas between which the good stuff appears are those after “Keaton” and before “has died.” The other commas, and the words between them, represent the writer and/or editor’s determination to cram a bunch of other stuff into that all-important first paragraph. The result is an unwieldy, 54-word opening sentence. Had I been the editor, I would have removed the clause starting with “an almost equal balance” and ending with “Marvin’s Room,” moving those interesting but non-essential facts deeper into the piece. But no one asked me.

A milder strain of the same virus infected the Times’s obituary of Robert Redford:

Robert Redford, the big-screen charmer turned Oscar-winning director whose hit movies often helped America make sense of itself and who, offscreen, evangelized for environmental causes and fostered the Sundance-centered independent film movement, died early Tuesday morning at his home in Utah. He was 89.

The first-sentence comma count is down to four; the word count is a reasonably manageable 41. And the Sundance stuff is a vital part of Redford’s legacy. So, we’ll leave this one be.

The Times, in an admirable attempt to help its readers understand its editorial process, has published an explanation of how it determines who qualifies for a news obit. This story, published in 2018, notes that the paper of record publishes an average of three of these obituaries a day, while the rest of the approximately 155,000 people who die on a given day don’t rate coverage. It continues:

There is no formula, scoring system or checklist. But we do hold to certain criteria, slippery as they may be. Fame, of the widespread kind, will usually get someone past the velvet ropes. Accomplishment, with wide impact, matters as much, and it often goes hand in hand with fame.

It’s hardly surprising that accomplishment, or achievement, plays a key role in determining whether a person’s death is newsworthy. We know Diane Keaton and Robert Redford through the roles they played; few of us know how they liked their coffee, or whether they were morning people or night owls.

Yet professional success and public notoriety are not the only measure of a life. Here’s the first paragraph of another recent obituary that also uses the “between the commas” format but applies different metrics:

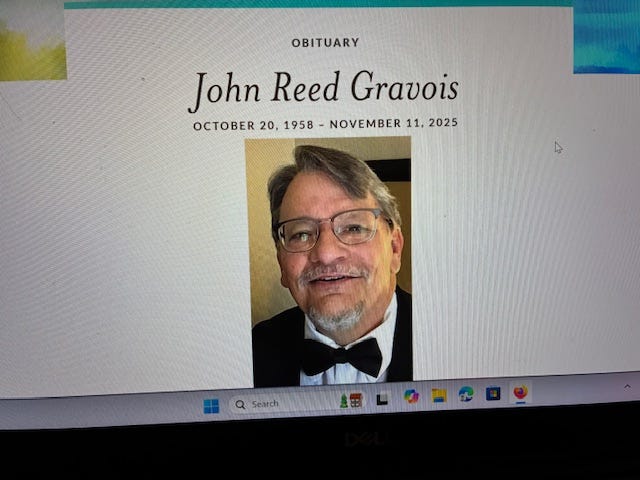

John Gravois, a proud son of Louisiana who loved the newspaper business and New Orleans football almost as much as he adored his family, died Tuesday, November 11, 2025. He was 67.

This was not a news obit; it was published at dignity.com, the website of a funeral planning company, and posted on Facebook. Although it carries no byline, it’s my understanding that a reporter wrote it; hence the “between the commas” approach.

I should note that John Gravois was a friend of mine, although we hadn’t been in touch very much recently. In the 1980s, we were competitors on the Houston City Hall news beat for several years; he worked for the Houston Post, I worked for the Chronicle. Our rivalry was fierce but friendly, underpinned by mutual respect. Many years later, John worked as an editor in the Chronicle’s Austin bureau, at a time when I was an editor on the Metro desk in Houston. We occasionally consulted about a story, but we never got together in person during this time, which I regret.

(He once referred to me as “wise” on social media. I have forgiven him.)

As I read his obituary, what stood out to me is what the writer — perhaps in consultation with family and friends — chose to put between those two all-important commas. We learn nothing about his professional achievements (detailed deeper in the obituary) except that he loved the newspaper business. He also loved New Orleans football and his family. He was proud of his South Louisiana heritage.

It’s entirely fitting, I think, that John’s obituary began by telling us some things about him that would resonate with those who loved him. He was a fine reporter and editor with many impressive career achievements, which are detailed in the obituary. But his work, impressive though it was, did not fully define him.

I was recently talking to my daughter, Megan, about her mother, Barbara Karkabi, who died of cancer in 2012. We recalled the chaos and constant sense of crisis that prevailed during the final year of her life, as her illness grew steadily worse and the likely outcome became more and more apparent. “You were a good husband,” Megan said to me. “You took good care of her.”

I’m proud of my career as a journalist, which has continued in a limited way since I retired from the Chronicle in 2019. But Megan’s words mean more to me than any professional achievement. I won’t be around to read it, but I’d love it if they could be prominently included in my obituary.